Connectivity Planning

There are many benefits to having connected, intact natural areas. Ecological connectivity supports biodiversity by allowing wildlife to move freely to access food, water, shelter, and breeding habitat. Connectivity also facilitates shifts in the ranges of plants, animals, and natural communities in response to environmental and climate change. People also benefit from the recreational and scenic values of large, contiguous natural areas. Finally, connected ecosystems are better able to function overall, and in turn continue to provide services that support human health and quality of life.

Describing Connectivity

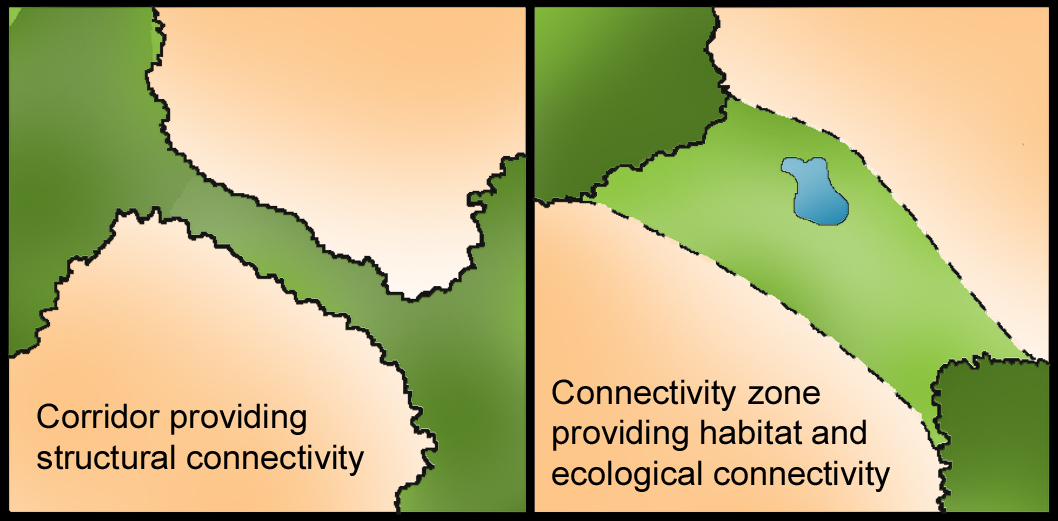

Connectivity is often characterized as structural or functional.

Structural connectivity considers the physical characteristics that support or impede a connected natural landscape, such as large forests, human development, and water bodies. In the absence of on-the-ground studies and data, structural connectivity is often estimated through computer modelling and mapping.

Functional connectivity describes how well a landscape allows for movement of organisms and processes such as seed dispersal, breeding migrations, and genetic exchange. This is a data-driven measure that requires study and monitoring to understand how species interact with the landscape.

Connectivity Examples in the Estuary Watershed

Connectivity is important at all scales. Here are just a few of the many examples of ecological connections that support biodiversity in the Hudson River estuary watershed:

- free-flowing streams where river herring return from the ocean to spawn each spring

- unfragmented forests where species like spotted salamander can safely migrate to woodland pools for breeding and forest interior birds can nest successfully

- wetland-upland habitat complexes where semi-aquatic turtles like wood turtle or spotted turtle can make seasonal movements between nesting, summer dormancy, or overwintering sites

- riparian corridors where streams can expand into their floodplains during high flows, allowing for natural processes that maintain water quality, create habitat, and help to prevent property damage during intense storms

- large, natural landscapes where mammals like bobcat, black bear, and fisher have room to roam.

Connectivity Planning and Conservation

While there are many protected areas in the estuary watershed, they are often isolated and may be surrounded by development. In particular, the interconnecting lowland areas often receive less conservation attention than adjacent mountains and ridges.

"Ecological networks for conservation are more effective in achieving biodiversity conservation objectives than a disconnected collection of individual protected areas...because they connect populations, maintain ecosystem functioning and are more resilient to climate change."

Guidelines for Conserving Connectivity through Ecological Networks and Corridors (Hilty et al. 2020)

Large, connected networks of conserved lands are better able to support biodiversity and ecological function than fragmented natural areas. This requires cooperative partnerships and diverse approaches, working at local, regional, and ecoregional scales to conserve and restore connectivity. Here are some examples:

- Municipalities and counties can include connectivity conservation as a goal in their comprehensive and open space plans, and use zoning techniques that prevent fragmentation.

- Land trusts can collaborate with local communities to facilitate conservation and land-use planning that supports connectivity and aligns local and regional strategies. Efforts can be made to conserve lands that are contiguous with protected lands.

- Watershed groups, municipalities, agencies, land trusts, and landowners can become familiar with important linkages, connectivity goals, and data sets and incorporate them into land protection, stewardship, and management goals. Sources of information include our Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Framework, Natural Resource Mapper, and biological data sets; the NYS Open Space Conservation Plan; and The Nature Conservancy’s Resilient and Connected Landscapes reports and data.

- Transportation agency partnerships can address issues such as wildlife mortality on roads and poorly-designed culverts that impact stream habitat.

- Communities, land trusts, landowners, and watershed groups can identify opportunities to restore connectivity, such as planting vegetation along streams where there are gaps in riparian habitat. Such restoration opportunities can be informed by the natural resources inventory process.

- Education and hands-on volunteer opportunities can help to increase awareness about the value of connectivity such as the Estuary Program’s Amphibian Migrations and Road Crossings Project or American Eel Project, or through local stewardship projects like Pollinator Pathways or use of camera traps to learn what wildlife are moving through the community.

Connectivity Planning in Practice

The Taghkanic Headwaters Conservation Plan creates a vision for the Taghkanic headwaters in Columbia County that engages local communities and landowners as stewards of clean water and connected habitats for fish and wildlife. The plan, completed in 2022 by Columbia Land Conservancy with funding from an Estuary Grant, maps five areas of exceptional importance including lands along the Taghkanic Creek, Pumpkin Hollow Swamp, and Copake Lake; and identifies conservation actions for individuals, groups, local governments, and conservation organizations.

The Green Corridors Plan for the Eastern New York Highlands identifies important links of natural lands like forests, marshes, and meadows between existing conserved lands in the eastern Hudson Highlands in Putnam County. The plan includes maps of key connections based on scientific analysis of critical areas for wildlife movement, conservation priorities of partner organizations, and input from the towns of Philipstown and Putnam Valley. The project, led by Hudson Highlands Land Trust, was completed in 2021 and funded by an Estuary Grant.

Hudson to Housatonic is an example of a Regional Conservation Partnership. The H2H mission is to advance regional land protection and stewardship from the Hudson River in New York to the Housatonic River in Connecticut by collaborating across boundaries.

The Town of Wawarsing (Ulster County) adopted two Critical Environmental Areas in 2019 to add protection to large, contiguous areas of habitat, including a regionally-important landscape connection between the Catskill Mountains and the Shawangunk Ridge. These areas were mapped and prioritized in the town’s Open Space Plan (2018), which received technical and funding assistance from the Estuary Program. The project is profiled in a video on DEC YouTube.

The Town and Village of Red Hook and Village of Tivoli (Dutchess County) took advantage of a pilot project funded by the Estuary Program in 2014, which applied the results of a Cornell local habitat connectivity model. Conservation opportunities were then identified through stakeholder engagement and recommendations were described in Planning for Resilient, Connected Natural Areas and Habitats: A Conservation Framework. Linkages identified in the model were incorporated into the biodiversity criteria used to rank acquisition priorities in the communities' 2016 Community Preservation Plan Update.

The Town and Village of New Paltz (Ulster County) proactively identified opportunities to conserve connected open space along a priority tributary in the community. Through a cooperative planning process that involved working with multiple landowners to acquire land or design conservation easements, the Mill Brook Preserve was formed in 2015, protecting more than 150 acres of forest, wetland, and stream habitat and providing walking trails for residents and visitors.

Helpful Links

Guidelines for Conserving Connectivity through Ecological Networks and Corridors (Hilty et al. 2020)

Nature Across Boundaries: Keeping Lands and Waters Connected (2017 conference presentations)

The Nature Conservancy’s Resilient and Connected Landscapes reports and data (2016)

The Regional Conservation Partnership Handbook: 10 Steps to Effective and Enduring Collaborative Conservation at Scale (Labich 2015)

Connectivity of Streams and Wetlands to Downstream Waters: A Review and Synthesis of the Scientific Evidence (USEPA 2015)

Aquatic Connectivity and Barrier Removal (NYSDEC website)

Evaluating and Conserving Green Infrastructure Across the Landscape: A Practitioner's Guide (Firehock 2013)

PATHWAYS: Wildlife Habitat Connectivity in the Changing Climate of the Hudson Valley (Howard and Schlesinger 2012)

The Role of Landscape Connectivity in Planning and Implementing Conservation and Restoration Priorities (Rudnick et al. 2012)

Conservation Buffers: Design Guidelines for Buffers, Corridors, and Greenways (Bentrup 2008)

Hudson River Estuary Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Framework (Penhollow et al. 2006)